USA, 10 min

Directed by: Ralph Steiner

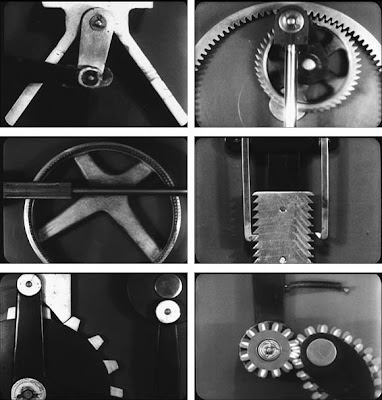

One might consider Mechnical Principles (1930) to be the converse of Ralph Steiner's most well-known work, H2O (1929). The latter film was a close-up examination of water, focusing intensely on the reflection and refraction of light by the liquid surface, an entirely natural substance that mesmerises through the sheer poetic randomness of its movements. There's nothing random about the mechanical movements of the former film. Cogs turn, pistons pump – repetitively and relentlessly, Mankind's constructions continue to carve perfect geometric circles. It's a bit like watching mathematics in motion. The transition between each shot is wonderfully smooth, the film constructed as a sort of mechanical waltz.

One might consider Mechnical Principles (1930) to be the converse of Ralph Steiner's most well-known work, H2O (1929). The latter film was a close-up examination of water, focusing intensely on the reflection and refraction of light by the liquid surface, an entirely natural substance that mesmerises through the sheer poetic randomness of its movements. There's nothing random about the mechanical movements of the former film. Cogs turn, pistons pump – repetitively and relentlessly, Mankind's constructions continue to carve perfect geometric circles. It's a bit like watching mathematics in motion. The transition between each shot is wonderfully smooth, the film constructed as a sort of mechanical waltz.Around this time, Hollywood directors like Busby Berkeley were engineering extravagant musical numbers in which dancers were utilised as mere cogs in a machine, each movement dependent upon the ability of the individual dancers to perform their role without error. In Mechanical Principles, this perfection is assured, for Man has never been able to replicate the precision of his machines. I've always found it fascinating how two men can view the same thing through very different eyes. There's something almost affectionate about how Steiner frames the perfectly-weighted movement of the factory machinery, and yet this is the same sort of industrial monotony against which Charles Chaplin campaigned in Modern Times (1936). Maybe both artists are right. Mechanical Principles is surely a mesmerising ten minutes, but, had it gone on for much longer, I might have ended up as hopelessly deranged as Chaplin's Little Tramp.

7/10

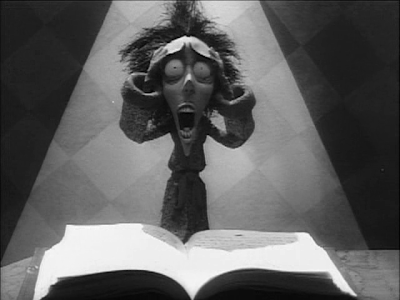

Vincent (1982) isn't the sort of film that you'd expect to come out of Walt Disney Productions, but it's exactly what you'd expect from Tim Burton. The director's first success, this six-minute animated short is both an affectionate tribute to the acting career of Vincent Price, and a vehicle for Burton's perverse sense of black humour. Vincent Malloy is a seven-year-old boy with an unhealthy obsession with the actor who shares his name, such that he actively wishes to become Vincent Price – or, more accurately, the range of characters that Price so memorably brought to the silver screen. Via increasingly-ghoulish flights of imagination, young Vincent envisages mutating his dog into a zombie henchman, dipping his auntie into hot wax, and attempting to dig up the totting corpse of his dead wife. Unfortunately, I'm not familiar enough with Price's body of work to spot all the references, but I'm fairly certain that among the movies Burton had in mind were House of Wax (1953), House of Usher (1960), The Last Man on Earth (1964) and, of course, The Raven (1963).

Vincent (1982) isn't the sort of film that you'd expect to come out of Walt Disney Productions, but it's exactly what you'd expect from Tim Burton. The director's first success, this six-minute animated short is both an affectionate tribute to the acting career of Vincent Price, and a vehicle for Burton's perverse sense of black humour. Vincent Malloy is a seven-year-old boy with an unhealthy obsession with the actor who shares his name, such that he actively wishes to become Vincent Price – or, more accurately, the range of characters that Price so memorably brought to the silver screen. Via increasingly-ghoulish flights of imagination, young Vincent envisages mutating his dog into a zombie henchman, dipping his auntie into hot wax, and attempting to dig up the totting corpse of his dead wife. Unfortunately, I'm not familiar enough with Price's body of work to spot all the references, but I'm fairly certain that among the movies Burton had in mind were House of Wax (1953), House of Usher (1960), The Last Man on Earth (1964) and, of course, The Raven (1963). The Soul of the Cypress (1921) reminds me of two Dimitri Kirsanoff short films from the mid-1930s.

The Soul of the Cypress (1921) reminds me of two Dimitri Kirsanoff short films from the mid-1930s.  The animated short films of John and Faith Hubley (here credited as Faith Elliott) have an air of improvisation about them. While some, like

The animated short films of John and Faith Hubley (here credited as Faith Elliott) have an air of improvisation about them. While some, like  Here's a little treasure that's rarely been allowed outside the Disney Vault. When watching Cannibal Capers (1930), one is faced with two options: you can be angered by the cartoonish racial stereotypes, or you can simply laugh, as I did, at the silliness of it all. Nowadays, most viewers are willing to dismiss perceived racism as "a sign of the times," but I think, particularly in this case, to do so is to do both Walt Disney and 1930s audiences a disservice. The caricatures of African tribesmen in Cannibal Capers are so outlandishly exaggerated that they could only have been intended as a spoof, perhaps satirising the xenophobic generalisations that were admittedly prevalent in the popular culture of the time (and they're still around today, so don't feel too vindicated). This cartoon, in line with many of the earliest Silly Symphonies, simply chooses a setting and devotes its inhabitants to a few minutes of dancing: The Skeleton Dance (1929) had skeletons, Hell's Bells (1929) had scary imps, Flowers and Trees (1932) had plants… and so Cannibal Capers has cannibals.

Here's a little treasure that's rarely been allowed outside the Disney Vault. When watching Cannibal Capers (1930), one is faced with two options: you can be angered by the cartoonish racial stereotypes, or you can simply laugh, as I did, at the silliness of it all. Nowadays, most viewers are willing to dismiss perceived racism as "a sign of the times," but I think, particularly in this case, to do so is to do both Walt Disney and 1930s audiences a disservice. The caricatures of African tribesmen in Cannibal Capers are so outlandishly exaggerated that they could only have been intended as a spoof, perhaps satirising the xenophobic generalisations that were admittedly prevalent in the popular culture of the time (and they're still around today, so don't feel too vindicated). This cartoon, in line with many of the earliest Silly Symphonies, simply chooses a setting and devotes its inhabitants to a few minutes of dancing: The Skeleton Dance (1929) had skeletons, Hell's Bells (1929) had scary imps, Flowers and Trees (1932) had plants… and so Cannibal Capers has cannibals. My first film from director Oskar Fischinger {though he did work on Lang's Frau im Mond (1929)} is, I hear, characteristic of his career in film: abstract animation synchronised to a musical rhythm. Allegretto (1936), his first project following his arrival in Hollywood, was originally commissioned as a segment of Paramount's The Big Broadcast of 1937 (1936), but the production was later changed from Technicolor to black-and-white, and only a butchered version of Fischinger's film found its way into the final release. In any case, to deprive the animation of its colours is to remove most of its charm, something akin to watching Fantasia (1940) in greyscale. Fischinger uses the movement of geometric shapes to visually represent music melodies, in this case Ralph Rainger's "Radio Dynamics," but it's the breathtakingly vivid colours that most strongly capture the pulsating energy of the jazz tune.

My first film from director Oskar Fischinger {though he did work on Lang's Frau im Mond (1929)} is, I hear, characteristic of his career in film: abstract animation synchronised to a musical rhythm. Allegretto (1936), his first project following his arrival in Hollywood, was originally commissioned as a segment of Paramount's The Big Broadcast of 1937 (1936), but the production was later changed from Technicolor to black-and-white, and only a butchered version of Fischinger's film found its way into the final release. In any case, to deprive the animation of its colours is to remove most of its charm, something akin to watching Fantasia (1940) in greyscale. Fischinger uses the movement of geometric shapes to visually represent music melodies, in this case Ralph Rainger's "Radio Dynamics," but it's the breathtakingly vivid colours that most strongly capture the pulsating energy of the jazz tune.

_poster.jpg)